Bowen + FrIedman

Systems Mentors

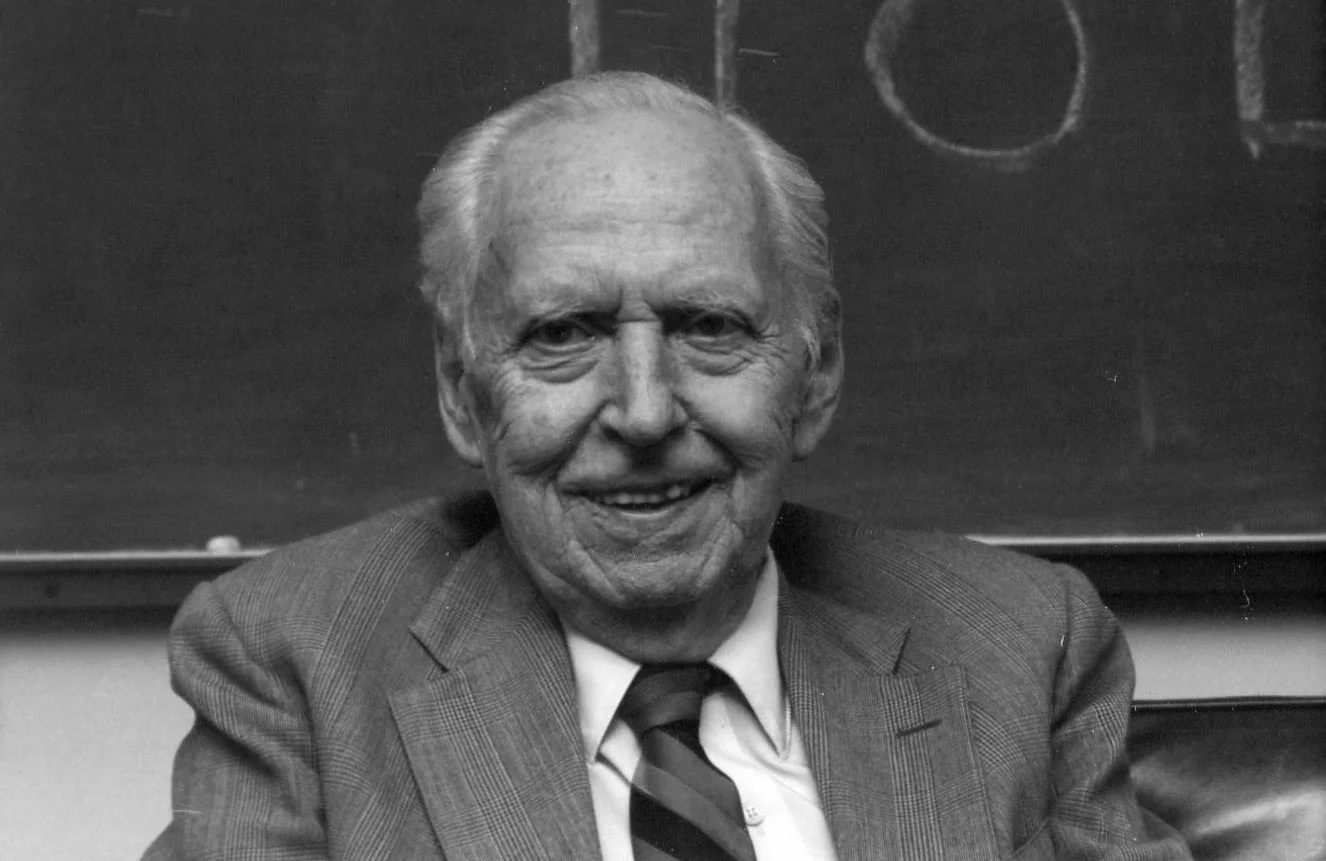

Many thanks to Andrea Schara for the many photos of Murray Bowen from her soon to be published collection

Many thanks to Andrea Schara for the many photos of Murray Bowen from her soon to be published collection

“If my hypothesis about societal anxiety is reasonably accurate, the crises of society will recur and recur, with increasing intensity for decades to come. Man created the environmental crisis by being the kind of creature he is. The environment is part of man, change will require a change in the basic nature of man, and man’s track record for that kind of thing has not been good. …I believe man is moving into crises of unparalleled proportions, that the crises will be different than those he has faced before, that they will come with increasing frequency for several decades… The type of man who survives that will be one who can live in better harmony with nature.”

Murray Bowen was born in Waverly, Tennessee to a family that had been in Middle Tennessee since the Revolution. Waverly, which is located about sixty miles west of Nashville in Humphreys County, was a town of approximately 1000 inhabitants in 1913 when Murray Bowen was born. He was the oldest of Jess Sewell Bowen’s and Maggie May Luff Bowen’s five children. He attended primary and secondary schools in Waverly, earned a B.S. degree from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville in 1934, and an M.D. from the University of Tennessee Medical School, Memphis in 1937. He then interned at Bellevue Hospital in New York City in 1938 and at the Grasslands Hospital in Valhalla, New York from 1939-41.

Following medical training, Murray Bowen served five years of active duty with the Army during World War II, 1941-46. He served in the United States and Europe, rising from the rank of Lieutenant to Major. He had been accepted for a fellowship in surgery at the Mayo Clinic to begin after military service, but Bowen’s wartime experiences resulted in a change of interest from surgery to psychiatry.

His psychiatric training was at the Menninger Foundation in Topeka, Kansas, beginning in 1946. He became a staff member upon completion of his formal training–although he had assumed staff-level responsibilities while still in a training status–and remained at Menninger’s until 1954. He then embarked on a unique five-year research project at the National Institute of Mental Health in Bethesda, Maryland. The project involved families with an adult schizophrenic child living on a research ward for long periods of time.

Bowen left N.I.M.H. in 1959 to become a half-time faculty member in the Department of Psychiatry at Georgetown University Medical Center. He became a Clinical Professor, was Director of Family Programs, and in 1975 founded the Georgetown Family Center. Dr. Bowen was the Director of the Family Center until his death. He also maintained a private psychiatric practice at his home-office in Chevy Chase, Maryland.

He was Visiting Professor in a variety of medical schools including the University of Maryland, 1956-1963; and part-time Professor and Chairman, Division of Family and Social Psychiatry, Medical College of Virginia, Richmond, from 1964to 1978. While at MCV he pioneered the use of closed-circuit television in family therapy. Television was used to integrate family therapy with family theory.

Murray Bowen was a scholar, researcher, clinician, teacher, and writer. He worked tirelessly toward a science of human behavior, one that viewed man as a part of all life. He was very active in professional organizations, always wanting to contribute in any way he could, usually trying to remind himself that there was only so much he could do. He was a life fellow of the American Psychiatric Association, the American Orthopsychiatric Association and the Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry. He served two consecutive terms as the first President of the American Family Therapy Association. His activities and prolific writings led to many awards and much recognition. He was recognized as Alumnus of the Year by the Menninger Foundation in 1985 and received the Distinguished Alumnus Award from the University of Tennessee-Knoxville in 1986.

He has been credited as being one of those rare human beings who had a genuinely new idea. He had the courage to go against the psychiatric and societal mainstream, to stand up for what he believed about human behavior. Thanks to his efforts the world has been rewarded with a new theory of human behavior, one with the potential to replace Freudian theory with a radically new method of psychotherapy based on the new theory.

Edwin Howard Friedman (May 17, 1932[1] – October 31, 1996) was an ordained Jewish Rabbi, family therapist, and leadership consultant. He was born in New York City and worked for more than 35 years in the Washington DC area where he founded the Bethesda Jewish Congregation. His primary areas of work were in family therapy, congregational leadership (both Christian and Jewish), and leadership more generally.

Friedman's approach was primarily shaped by an understanding of family systems theory. His seminal work Generation to Generation, written for the leaders of religious congregations, focused on leaders developing three main areas of themselves:

Being self differentiated

Being non-anxious

Being present with those one is leading

Building on his work, Generation to Generation, Friedman's family and friends published A Failure of Nerve--leadership in the age of the quick fix finishing Friedman's work on his understanding of leaders as "self-differentiated or well-differentiated."

Friedman illustrates good “self-differentiated” leadership to that present in the great Renaissance explorers, where leaders had:

the capacity to separate oneself from surrounding emotional processes

the capacity to obtain clarity about one’s principles and vision

the willingness to be exposed and be vulnerable

the persistence to face inertial resistance

the self-regulation of emotions in the face of reactive sabotage.

Two concepts are critical in Friedman’s model: self-knowledge and self-control. Friedman attacks what he calls the failure of nerve in leaders who are “highly anxious risk-avoiders,” more concerned with good feelings than with progress–one whose life revolves around the axis of consensus. By self-differentiation, the leader maintains his/her integrity (a non-anxious self as opposed to an anxious non-self) and thus promotes “the integrity or prevents the dis-integr-ation of the system he or she is leading."

In other places, Friedman argues that the well-differentiated leader:

“...is not an autocrat who tells others what to do or orders them around, although any leader who defines himself or herself clearly may be perceived that way by those who are not taking responsibility for their own emotional being and destiny... is someone who has clarity about his or her own life goals, and, therefore, someone who is less likely to become lost in the anxious emotional processes swirling about.... is someone who can separate while still remaining connected, and therefore can maintain a modifying, non-anxious, and sometimes challenging presence... is someone who can manage his or her own reactivity to the automatic reactivity of others, and therefore be able to take stands at the risk of displeasing.”